Dolphins

Dolphins are marine mammals that are closely related to whales and porpoises. There are almost forty species of dolphin in seventeen genera. They vary in size from 1.2 metres (4 ft) and 40 kilograms (88 lb) (Maui's Dolphin), up to 9.5 m (30 ft) and ten tonnes (the Orca or Killer Whale). They are found worldwide, mostly in the shallower seas of the continental shelves, and are carnivores, mostly eating fish and squid. The family Delphinidae is the largest in the Cetacea, and relatively recent: dolphins evolved about ten million years ago, during the Miocene. Dolphins are considered to be amongst the most intelligent of animals and their often friendly appearance and seemingly playful attitude have made them popular in human culture.

Scientists find out that dolphins 'talk' like humans MSNBC - September 7, 2011

Dolphins do not whistle, but instead "talk" to each other using a process very similar to the way that humans communicate, according to a new study. While many dolphin calls sound like whistles, the study found the sounds are produced by tissue vibrations analogous to the operation of vocal folds by humans and many other land-based animals.

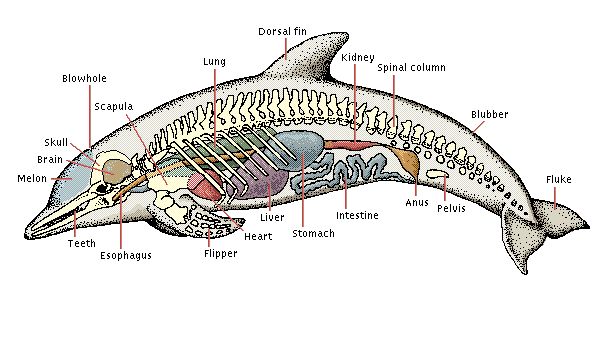

Dolphins are capable of making a broad range of sounds using nasal airsacs located just below the blowhole. Roughly three categories of sounds can be identified: frequency modulated whistles, burst-pulsed sounds and clicks. Dolphins communicate with their whistles and burst-pulsed sounds, though the nature and extent of that ability is not known. At least some dolphin species can identify themselves using a signature whistle. The clicks are directional and are for echolocation, often occurring in a short series called a click train. The click rate increases when approaching an object of interest. Dolphin echolocation clicks are amongst the loudest sounds made by marine animals.

Dolphins emit pulses of sound from the melon, a fatty area just below the blowhole. Much like the orientation vocalizations of a bat, these pulses, or clicks, return as echoes when the sound bounces off objects in the dolphin's path. The animal uses the echoes to navigate and to judge the distance to, and location of, prey as small as shrimp. Dolphins also produce whistling sounds when excited or communicating with other dolphins. These sounds arise from the larynx.

Dolphins almost constantly emit either clicking sounds or whistles. The clicks are short pulses of about 300 sounds per second, emitted from a mechanism located just below the blowhole. These clicks are used for the echolocation of objects and are resonated forward by the so-called oily melon, which is located above the forehead and acts as an acoustic lens. Echoes received at the area of the rear of the lower jaw are transmitted by a fat organ in the lower jaw to the middle ear. This echolocation system, similar to that of a bat, enables the dolphin to navigate among its companions and larger objects and to detect fish, squid, and even small shrimp. The whistles are single-toned squeals that come from deeper in the larynx. They are used to communicate alarm, sexual excitement, and perhaps other emotional states.

Because of the ability of dolphins to learn and perform complex tasks in captivity, their continuous communications with one another, and their ability, through training, to approximate the sounds of a few human words, some investigators have suggested that the animals might be capable of learning a true language and communicating with humans. Most authorities, however, agree that although the dolphin's problem-solving abilities put the animal on an intelligence level close to that of primates, no evidence exists that dolphin communications approach the complexity of a true language.

Dolphins - Healing, Metaphysics, and Mythology

Most dolphins have acute eyesight, both in and out of the water, and they can hear frequencies ten times or more above the upper limit of adult human hearing.

Though they have a small ear opening on each side of their head, it is believed hearing underwater is also, if not exclusively, done with the lower jaw, which conducts sound to the middle ear via a fat-filled cavity in the lower jaw bone. Hearing is also used for echolocation, which all dolphins have.

Dolphin teeth are believed to function as antennae to receive incoming sound and to pinpoint the exact location of an object.

The dolphin's sense of touch is also well-developed, with free nerve endings densely packed in the skin, especially around the snout, pectoral fins and genital area. However, dolphins lack an olfactory nerve and lobes, and thus are believed to have no sense of smell.

They have a sense of taste and show preferences for certain kinds of fish. Since dolphins spend most of their time below the surface, tasting the water could function like smelling, in that substances in the water can signal the presence of objects that are not in the dolphinÕs mouth.

Though most dolphins do not have hair, they do have hair follicles that may perform some sensory function.[20] The small hairs on the rostrum of the Boto river dolphin are believed to function as a tactile sense possibly to compensate for the Boto's poor eyesight.

Dolphins are often regarded as one of Earth's most intelligent animals, though it is hard to say just how intelligent. Comparing species' relative intelligence is complicated by differences in sensory apparatus, response modes, and nature of cognition. Furthermore, the difficulty and expense of experimental work with large aquatic animals has so far prevented some tests and limited sample size and rigor in others. Compared to many other species, however, dolphin behavior has been studied extensively, both in captivity and in the wild.

Dolphins are social, living in pods of up to a dozen individuals. In places with a high abundance of food, pods can merge temporarily, forming a superpod; such groupings may exceed 1,000 dolphins. Individuals communicate using a variety of clicks, whistles and other vocalizations. They make ultrasonic sounds for echolocation. Membership in pods is not rigid; interchange is common.

However, dolphins can establish strong social bonds; they will stay with injured or ill individuals, even helping them to breathe by bringing them to the surface if needed. This altruism does not appear to be limited to their own species however. The dolphin Moko in New Zealand has been observed guiding a female Pygmy Sperm Whale together with her calf out of shallow water where they had stranded several times. They have also been seen protecting swimmers from sharks by swimming circles around the swimmers or charging the sharks to make them go away.

Dolphins also display culture, something long believed to be unique to humans (and possibly other primate species). In May 2005, a discovery in Australia found Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus) teaching their young to use tools. They cover their snouts with sponges to protect them while foraging. This knowledge is mostly transferred by mothers to daughters, unlike simian primates, where knowledge is generally passed on to both sexes. Using sponges as mouth protection is a learned behavior. Another learned behavior was discovered among river dolphins in Brazil, where some male dolphins use weeds and sticks as part of a sexual display.

Dolphins engage in acts of aggression towards each other. The older a male dolphin is, the more likely his body is to be covered with bite scars. Male dolphins engage in such acts of aggression apparently for the same reasons as humans: disputes between companions and competition for females. Acts of aggression can become so intense that targeted dolphins sometimes go into exile as a result of losing a fight.

Male bottlenose dolphins have been known to engage in infanticide. Dolphins have also been known to kill porpoises for reasons which are not fully understood, as porpoises generally do not share the same diet as dolphins, and are therefore not competitors for food supplies.

In one day dolphins eat an amount of food, mostly fish and squid, equal to nearly one-third of their weight. Dolphins are swift enough to easily outdistance their prey. They seize their catches with jaws that have from 200 to 250 sharp teeth. Dolphins follow schools of fish in groups of varying size. Some species, such as the Pacific white-sided dolphin, make up aggregations estimated at tens of thousands of members. Less gregarious species, such as the bottle-nosed dolphin, join in groups that often contain only a few members.

Various methods of feeding exist among and within species, some apparently exclusive to a single population. Fish and squid are the main food, but the false killer whale and the orca also feed on other marine mammals.

One common feeding method is herding, where a pod squeezes a school of fish into a small volume, known as a bait ball. Individual members then take turns plowing through the ball, feeding on the stunned fish. Coralling is a method where dolphins chase fish into shallow water to more easily catch them. In South Carolina, the Atlantic bottlenose dolphin takes this further with "strand feeding", driving prey onto mud banks for easy access.

In some places, orcas come to the beach to capture sea lions. Some species also whack fish with their flukes, stunning them and sometimes knocking them out of the water.

Reports of cooperative human-dolphin fishing date back to the ancient Roman author and natural philosopher Pliny the Elder. A modern human-dolphin partnership currently operates in Laguna, Santa Catarina, Brazil. Here, dolphins drive fish towards fishermen waiting along the shore and signal the men to cast their nets. The dolphinsÕ reward is the fish that escape the nets.

Dolphins, like whales, breathe through a blowhole at the top of the head. As they travel they break surface about every two minutes to make a short, explosive exhalation, followed by a longer inhalation before submerging again.

The tail, like that of other aquatic mammals, strokes in an up-and-down motion, with the double flukes driving the animal forward; the flippers are used for stabilization. Dolphins are superbly streamlined and can sustain speeds of up to 30 km/h (up to 19 mph), with bursts of more than 40 km/h (more than 25 mph). Their lungs, which are adapted to resist the physical problems created for many animals by rapid changes in pressure, enable them to dive to depths of more than 300 m (more than 1000 ft).

Adults of the bottle-nosed dolphin - the best-studied species -come to sexual maturity after 5 to 12 years in females and 9 to 13 years in males. They mate in the spring; after a gestation period of 11 or 12 months, a single calf is born, tail first. Calves swim and breathe minutes after birth; they nurse for up to 18 months. They are able to keep up with the mother by remaining close and taking advantage of the aerodynamic effects of the mother's swimming.

Generally, dolphins sleep with only one brain hemisphere in slow-wave sleep at a time, thus maintaining enough consciousness to breathe and to watch for possible predators and other threats. Earlier sleep stages can occur simultaneously in both hemispheres.

In captivity, dolphins seemingly enter a fully asleep state where both eyes are closed and there is no response to mild external stimuli. In this case respiration is automatic; a tail kick reflex keeps the blowhole above the water if necessary. Anesthetized dolphins initially show a tail kick reflex.

Though a similar state has been observed with wild Sperm Whales, it is not known if dolphins in the wild reach this state.

The Indus river dolphin has a different sleep method from other dolphin species. Living in water with strong currents and potentially dangerous floating debris, it must swim continuously to avoid injury. As a result, this species sleeps in very short bursts which last between 4 and 60 seconds.

Intelligence

Dolphin Studies Could Reveal Secrets of Extraterrestrial Intelligence Live Science - September 6, 2011

How do we define intelligence? SETI, the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence, clearly equates intelligence with technology (or, more precisely, the building of radio or laser beacons). Some, such as the science fiction writer Isaac Asimov, suggested that intelligence wasn't just the acquisition of technology, but the ability to develop and improve it, integrating it into our society.

By that definition, a dolphin, lacking limbs to create and manipulate complex tools, cannot possibly be described as intelligent. It's easy to see why such definitions prove popular; we are clearly the smartest creatures on the planet, and the only species with technology. It may be human hubris, or some kind of anthropocentric bias that we find difficult to escape from, but our adherence to this definition narrows the phase space in which we're willing to search for intelligent life.

No comments:

Post a Comment