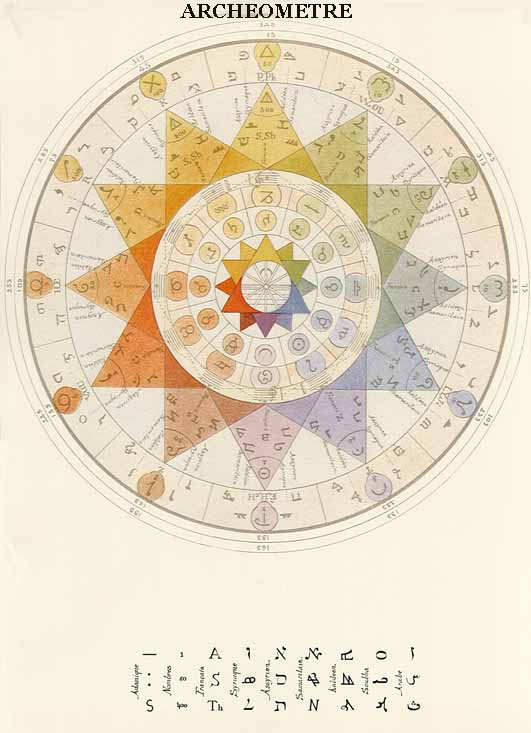

In the second decade of the twenty-first century, alchemy is not only about the transmutation of metals, but the shift in consciousness that returns us from the physical to the non-physical.

Throughout its history, alchemy has shown a dual nature. On the one hand, it has involved the use of chemical substances and so is claimed by the history of science as the precursor of modern chemistry. Yet at the same time, alchemy has, throughout its history, also been associated with the esoteric, spiritual beliefs of Hermeticism and thus is a proper subject for the historian of religious thought. Such an approach is complemented by the psychological studies of Carl Jung, which correlate alchemical symbolism with the development of the psycho-religious life of the individual.

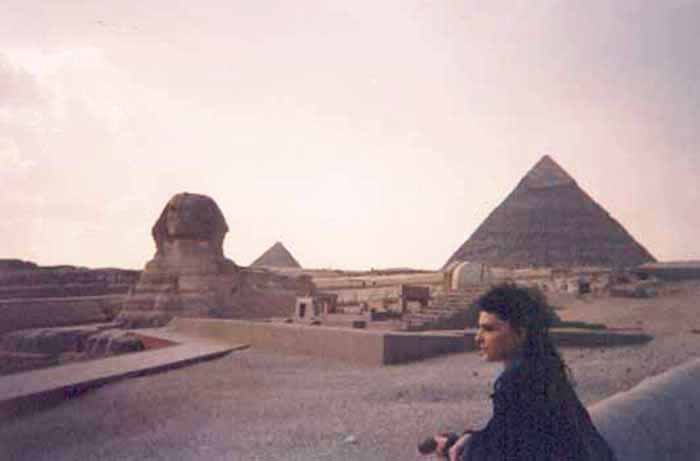

Alchemy was practiced in Mesopotamia, Ancient Egypt, Persia, India, Japan, Korea and China, in Classical Greece and Rome, in the Muslim civilizations, and then in Europe up to the 19th century in a complex network of schools and philosophical systems spanning at least 2,500 years.

In the history of science, alchemy refers to both an early form of the investigation of nature and an early philosophical and spiritual discipline, both combining elements of chemistry, metallurgy, physics, medicine, astrology, semiotics, mysticism, spiritualism, and art all as parts of one greater force.

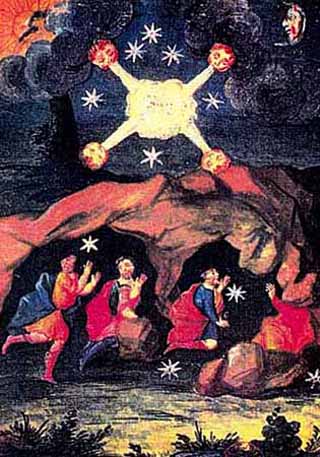

Alchemy is an ancient path of spiritual purification and transformation; the expansion of consciousness and the development of insight and intuition through images. Alchemy is steeped in mysticism and mystery. It presents to the initiate a system of eternal, dreamlike, esoteric symbols that have the power to alter consciousness and connect the human soul to the Divine.

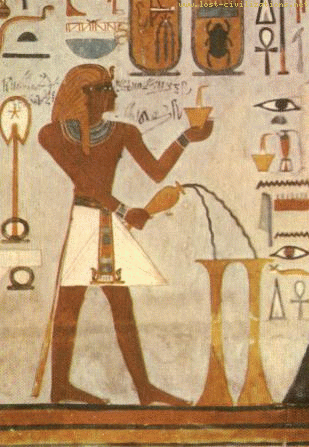

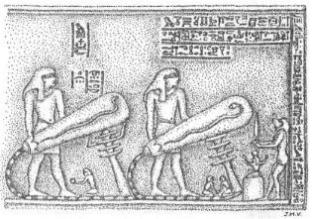

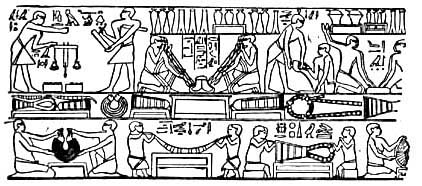

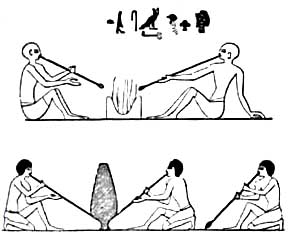

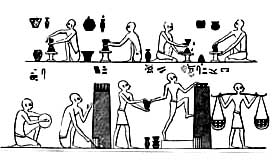

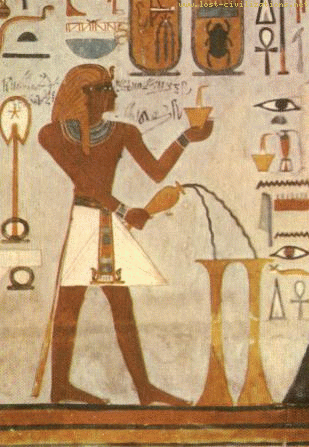

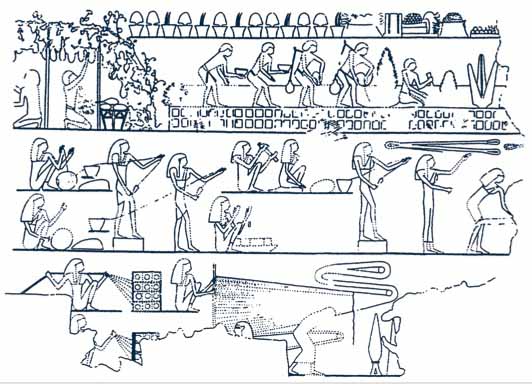

It is part of the mystical and mystery traditions of both East and West. In the West, it dates to ancient Egypt, where adepts first developed it as an early form of chemistry and metallurgy. Egyptians alchemists used their art to make alloys, dyes, perfumes and cosmetic jewelry, and to embalm the dead.

The early Arabs made significant contributions to alchemy, such as by emphasizing the mysticism of numbers (quantities and lengths of time for processes). The Arabs also gave us the term 'alchemy', from the Arabic term 'alchimia', which loosely translated means 'the Egyptian art'.

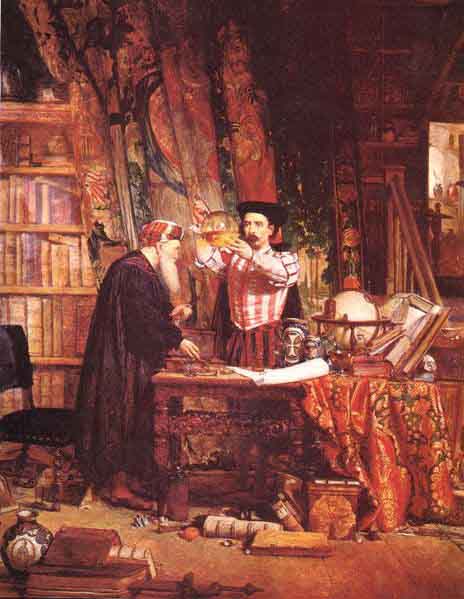

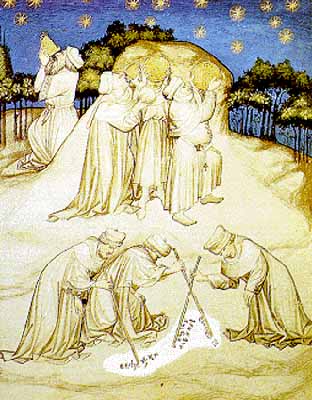

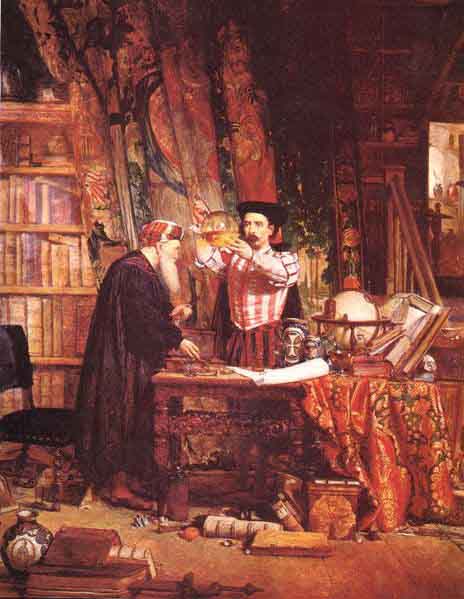

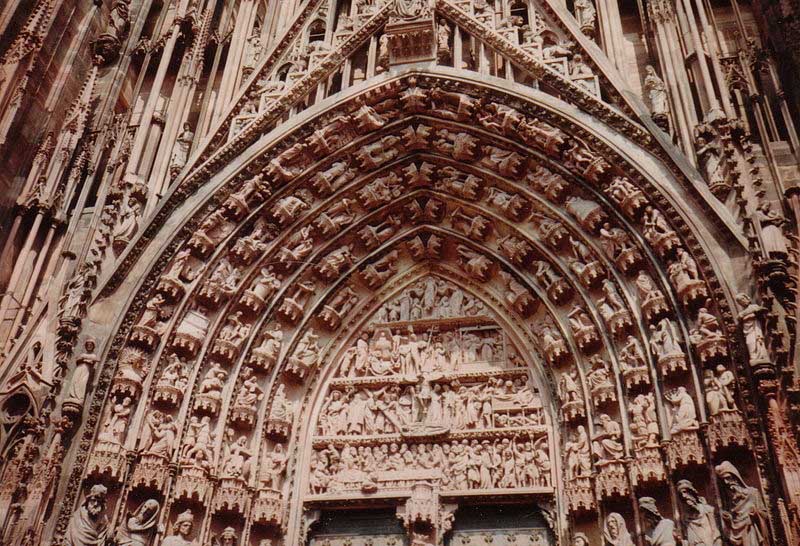

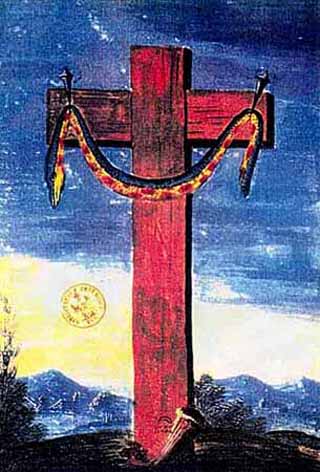

During medieval and Renaissance times, alchemy spread through the Western world, and was further developed by Kabbalists, Rosicrucians, astrologers and other occultists. It functioned on two levels: mundane and spiritual. On a mundane level, alchemists sought to find a physical process to convert base metals such as lead into gold. On a spiritual level, alchemists worked to purify themselves by eliminating the "base" material of the self and achieving the 'gold' of enlightenment.

By Renaissance times, many alchemists believed that the spiritual purification was necessary in order to achieve the mundane transformations of metals.

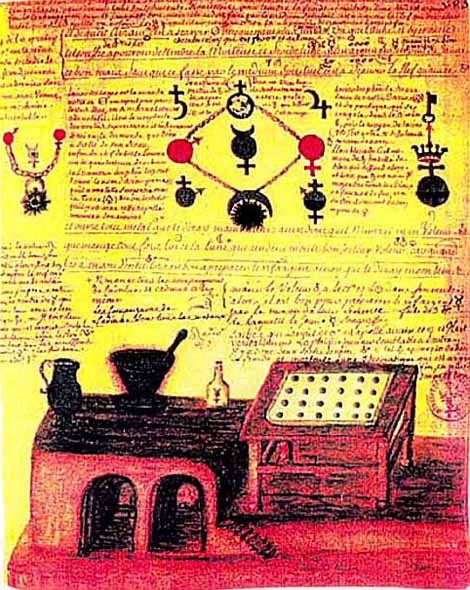

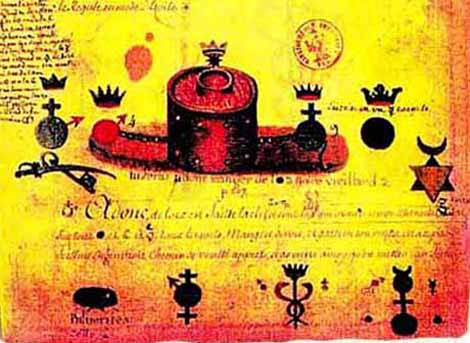

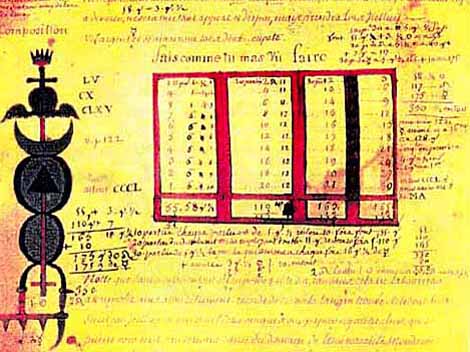

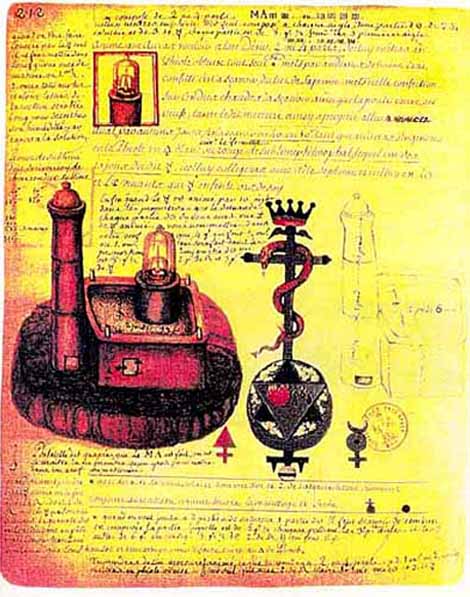

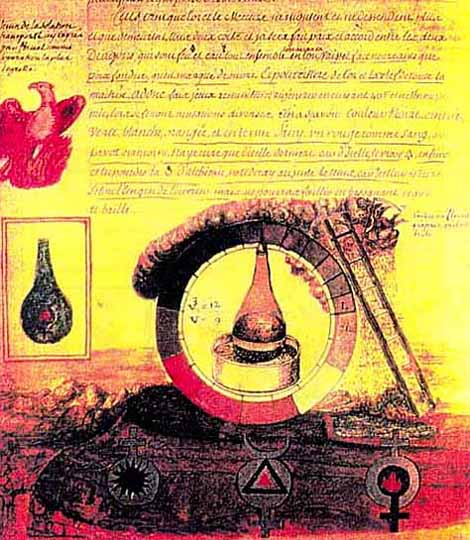

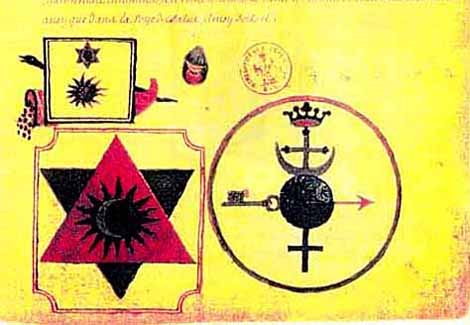

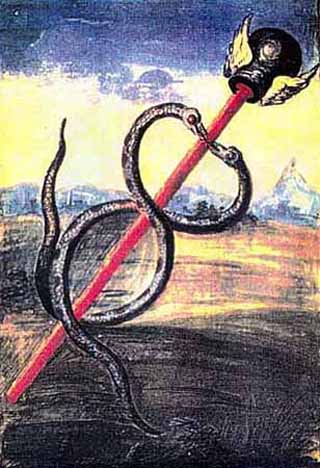

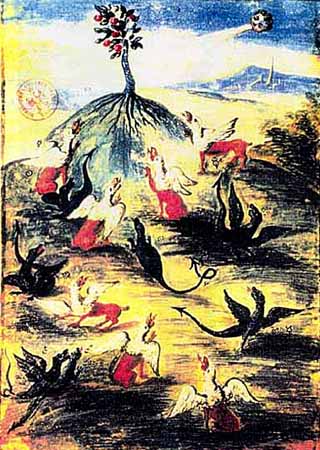

The alchemists relied heavily upon their dreams, inspirations and visions for guidance in perfecting their art. In order to protect their secrets, they recorded diaries filled with mysterious symbols rather than text. These symbols remain exceptionally potent for changing states of consciousness.

Alchemy is a form of speculative thought that, among other aims, tried to transform base metals such as lead or copper into silver or gold and to discover a cure for disease and a way of extending life.

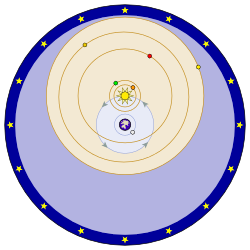

Alchemy was the name given in Latin Europe in the 12th century to an aspect of thought that corresponds to astrology, which is apparently an older tradition. Both represent attempts to discover the relationship of man to the cosmos and to exploit that relationship to his benefit. The first of these objectives may be called scientific, the second technological.

Astrology is concerned with man's relationship to "the stars" (including the members of the solar system); alchemy, with terrestrial nature. But the distinction is far from absolute, since both are interested in the influence of the stars on terrestrial events. Moreover, both have always been pursued in the belief that the processes human beings witness in heaven and on earth manifest the will of the Creator and, if correctly understood, will yield the key to the Creator's intentions.

Nature and Significance

Evidence from ancient Middle America (Aztecs, Mayans) is still almost nonexistent; evidence from India is tenuous and from ancient China, Greece, and Islamic lands is only relatively more plentiful.

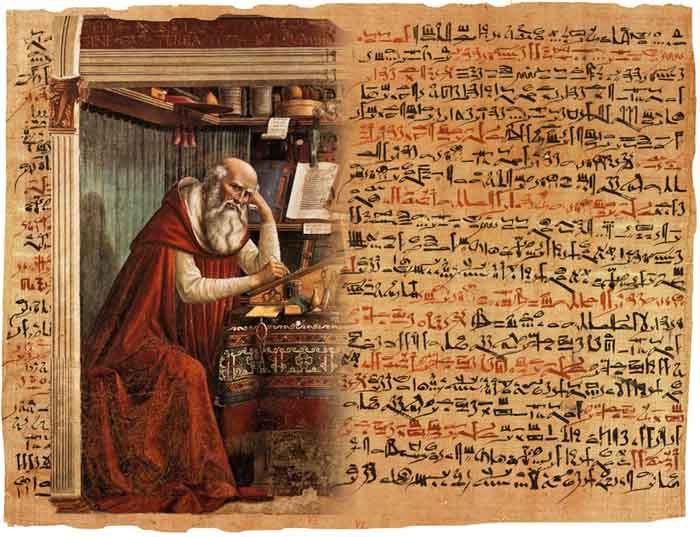

A single manuscript of some 80,000 words is the principal source for the history of Greek alchemy.

Chinese alchemy is largely recorded in about 100 "books" that are part of the Taoist canon.

Neither Indian nor Islamic alchemy has ever been collected, and scholars are thus dependent for their knowledge of the subject on occasional allusions in works of natural philosophy and medicine, plus a few specifically alchemical works.

Nor is it really clear what alchemy was (or is). The word is a European one, derived from Arabic, but the origin of the root word, chem, is uncertain. Words similar to it have been found in most ancient languages, with different meanings, but conceivably somehow related to alchemy. In fact, the Greeks, Chinese, and Indians usually referred to what Westerners call alchemy as "The Art," or by terms denoting change or transmutation.

The Chemistry of Alchemy

Mercury, the liquid metal, certainly known before 300 BC, when it appears in both Eastern and Western sources, was crucial to alchemy. Sulfur, "the stone that burns," was also crucial. It was known from prehistoric times in native deposits and was also given off in metallurgic processes (the "roasting" of sulfide ores).

Mercury united with most of the other metals, and the amalgam formed colored powders (the sulfides) when treated with sulfur. Mercury itself occurs in nature in a red sulfide, cinnabar, which can also be made artificially. All of these, except possibly the last, were operations known to the metallurgist and were adopted by the alchemist.

The alchemist added the action on metals of a number of corrosive salts, mainly the vitriols (copper and iron sulfates), alums (the aluminum sulfates of potassium and ammonium), and the chlorides of sodium and ammonium. And he made much of arsenic's property of colouring metals. All of these materials, except the chloride of ammonia, were known in ancient times.

Known as sal ammoniac in the West, nao sha in China, nao sadar in India, and nushadir in Persia and Arabic lands, the chloride of ammonia first became known to the West in the Chou-i ts'an t'ung ch'i, a Chinese treatise of the 2nd century AD.

It was to be crucial to alchemy, for on sublimation it dissociates into antagonistic corrosive materials, ammonia and hydrochloric acid, which readily attack the metals. Until the 9th century it seems to have come from a single source, the Flame Mountain (Huo-yen Shan) near T'u-lu-p'an (Turfan), in Central Asia.

Finally, the manipulation of these materials was to lead to the discovery of the mineral acids, the history of which began in Europe in the 13th century. The first was probably nitric acid, made by distilling together saltpetre (potassium nitrate) and vitriol or alum. More difficult to discover was sulfuric acid, which was distilled from vitriol or alum alone but required apparatus resistant to corrosion and heat. And most difficult was hydrochloric acid, distilled from common salt or sal ammoniac and vitriol or alum, for the vapours of this acid cannot be simply condensed but must be dissolved in water.

Goals

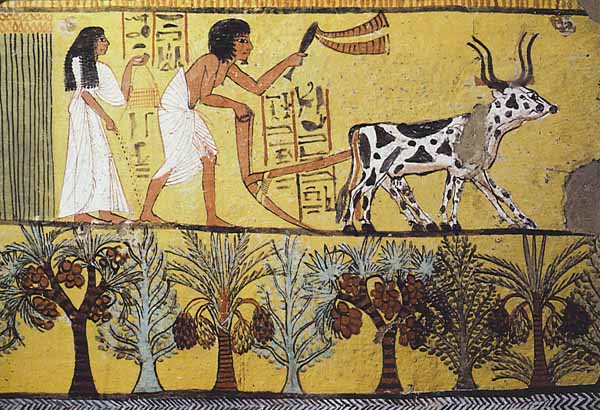

Alchemy was not original in seeking these goals, for it had been preceded by religion, medicine, and metallurgy. The first chemists were metallurgists, who were perhaps the most successful practitioners of the arts in antiquity. Their theories seem to have come not from science but from folklore and religion. The miner and metallurgist, like the agriculturalist, in this view, accelerate the normal maturation of the fruits of the earth, in a magico-religious relationship with nature. In primitive societies the metallurgist is often a member of an occult religious society.

But the first ventures into natural philosophy, the beginnings of what is called the scientific view, also preceded alchemy. Systems of five almost identical basic elements were postulated in China, India, and Greece, according to a view in which nature comprised antagonistic, opposite forces--hot and cold, positive and negative, and male and female; i.e., primitive versions of the modern conception of energy. Drawing on a similar astrological heritage, philosophers found correspondences among the elements, planets, and metals. In short, both the chemical arts and the theories of the philosophers of nature had become complex before alchemy appeared.

Regional Variations

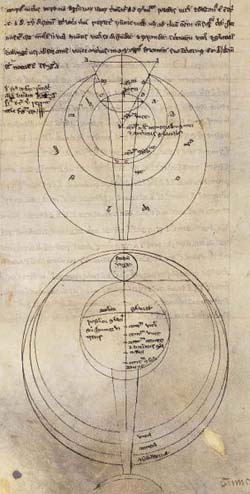

Chinese Alchemy

Although non-Chinese influences (especially Indian) are possible, the genesis of alchemy in China may have been a purely domestic affair. It emerged during a period of political turmoil, the Warring States Period (from the 5th to the 3rd century BC), and it came to be associated with Taoism--a mystical religion founded by the 6th-century-BC sage Lao-tzu--and its sacred book, the Tao-te Ching ("Classic of the Way of Power"). The Taoists were a miscellaneous collection of "outsiders"--in relation to the prevailing Confucians--and such mystical doctrines as alchemy were soon grafted onto the Taoist canon. What is known of Chinese alchemy is mainly owing to that graft, and especially to a collection known as Yün chi ch'i ch'ien ("Seven Tablets in a Cloudy Satchel"), which is dated 1023. Thus, sources on alchemy in China (as elsewhere) are compilations of much earlier writings.

The oldest known Chinese alchemical treatise is the Chou-i ts'an t'ung ch'i ("Commentary on the I Ching"). In the main it is an apocryphal interpretation of the I Ching ("Classic of Changes"), an ancient classic especially esteemed by the Confucians, relating alchemy to the mystical mathematics of the 64 hexagrams (six-line figures used for divination). Its relationship to chemical practice is tenuous, but it mentions materials (including sal ammoniac) and implies chemical operations.

The first Chinese alchemist who is reasonably well known was Ko Hung (AD 283-343), whose book Pao-p'u-tzu (pseudonym of Ko Hung) contains two chapters with obscure recipes for elixirs, mostly based on mercury or arsenic compounds.

The most famous Chinese alchemical book is the Tan chin yao chüeh ("Great Secrets of Alchemy"), probably by Sun Ssu-miao (AD 581-after 673). It is a practical treatise on creating elixirs (mercury, sulfur, and the salts of mercury and arsenic are prominent) for the attainment of immortality, plus a few for specific cures for disease and such other purposes as the fabrication of precious stones.

Altogether, the similarities between the materials used and the elixirs made in China, India, and the West are more remarkable than are their differences. Nonetheless, Chinese alchemy differed from that of the West in its objective. Whereas in the West the objective seems to have evolved from gold to elixirs of immortality to simply superior medicines, neither the first nor the last of these objectives seems ever to have been very important in China.

Chinese alchemy was consistent from first to last, and there was relatively little controversy among its practitioners, who seem to have varied only in their prescriptions for the elixir of immortality or perhaps only over their names for it, of which one Sinologist has counted about 1,000. In the West there were conflicts between advocates of herbal and "chemical" (i.e., mineral) pharmacy, but in China mineral remedies were always accepted.

In Europe, there were conflicts between alchemists who favoured gold making and those who thought medicine the proper goal, but the Chinese always favoured the latter. Since alchemy rarely achieved any of these goals, it was an advantage to the Western alchemist to have the situation obscured, and the art survived in Europe long after Chinese alchemy had simply faded away.

Chinese alchemy followed its own path. Whereas the Western world, with its numerous religious promises of immortality, never seriously expected alchemy to fulfill that goal, the deficiencies of Chinese religions in respect to promises of immortality left that goal open to the alchemist. A serious reliance on medical elixirs that were in varying degrees poisonous led the alchemist into permanent exertions to moderate those poisons, either through variation of the ingredients or through chemical manipulations.

The fact that immortality was so desirable and the alchemist correspondingly valued enabled the British historian of science Joseph Needham to tabulate a series of Chinese emperors who probably died of elixir poisoning. Ultimately a succession of royal deaths made alchemists and emperors alike more cautious, and Chinese alchemy vanished (probably as the Chinese adopted Buddhism, which offered other, less dangerous avenues to immortality), leaving its literary manifestations embedded in the Taoist canons.

Indian Alchemy

Evidence of the idea of transmuting base metals to gold appears in 2nd- to 5th-century-AD Buddhist texts, about the same time as in the West. Since Alexander the Great had invaded India in 325 BC, leaving a Greek state (Gandhara) that long endured, the possibility exists that the Indians acquired the idea from the Greeks, but it could have been the other way around.

It is also possible that the alchemy of medicine and immortality came to India from China, or vice versa; in any case, gold making appears to have been a minor concern, and medicine the major concern, of both cultures. But the elixir of immortality was of little importance in India (which had other avenues to immortality). The Indian elixirs were mineral remedies for specific diseases or, at the most, to promote long life.

As in China and the West, alchemy in India came to be associated with religious mysticism, but much later--not until the rise of Tantrism (an esoteric, occultic, meditative system), AD 1100-1300. To Tantrism are owed writings that are clearly alchemical (such as the 12th-century Rasarnava, or "Treatise on Metallic Preparations").

From the earliest records of Indian natural philosophy, which date from the 5th-3rd centuries BC, theories of nature were based on conceptions of material elements (fire, wind, water, earth, and space), vitalism ("animated atoms"), and dualisms of love and hate or action and reaction.

The alchemist colored metals and on occasion "made" gold, but he gave little importance to that. His six metals (gold, silver, tin, iron, lead, and copper), each further subdivided (five kinds of gold, etc.), were "killed" (i.e., corroded) but not "resurrected," as was the custom of Western alchemy. Rather, they were killed to make medicines. Although "the secrets of mercurial lore" became part of the Tantric rite, mercury seems to have been much less important than in China.

The Indians exploited metal reactions more widely, but, although they possessed from an early date not only vitriol and sal ammoniac but also saltpetre, they nevertheless failed to discover the mineral acids. This is the more remarkable because India was long the principal source of saltpetre, which occurs as an efflorescence on the soil, especially in populous tropical countries.

But it lacks the high degree of corrosivity of metals possessed by the vitriols and chlorides and played a small part in early alchemy. Saltpetre appears particularly in 9th- to 11th-century-AD Indian and Chinese recipes for fireworks, one of which--a mixture of saltpetre, sulfur, and charcoal--is gunpowder. Saltpetre first appears in Europe in the 13th century, along with the modern formula for gunpowder and the recipe for nitric acid.

Hellenistic Alchemy

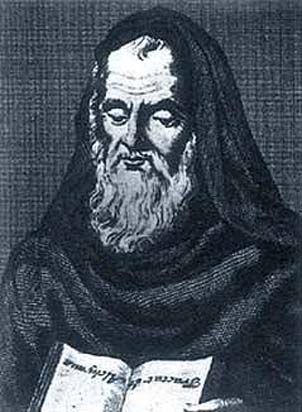

The earliest is the author designated Democritus but identified by scholars with Bolos of Mende, a Hellenized Egyptian who lived in the Nile Delta about 200 BC.

He is represented by a treatise called Physica et mystica ("Natural and Mystical Things"), a kind of recipe book for dyeing and colouring but principally for the making of gold and silver. The recipes are stated obscurely and are justified with references to the Greek theory of elements and to astrological theory.

Most end with the phrase "One nature rejoices in another nature; one nature triumphs over another nature; one nature masters another nature," which authorities variously trace to the Magi (Zoroastrian priests), Stoic pantheism (a Greek philosophy concerned with nature), or to the 4th-century-BC Greek philosopher Aristotle. It was the first of a number of such aphorisms over which alchemists were to speculate for many centuries.

In 1828 a group of ancient papyrus manuscripts written in Greek was purchased in Thebes (Egypt), and about a half-century later it was noticed that among them, divided between libraries in Leyden (The Netherlands) and Stockholm, was a tract very like the Physica et mystica. It differed, however, in that it lacked the former's theoretical embellishments and stated in some recipes that only fraudulent imitation of gold and silver was intended.

Scholars believe that this kind of work was the ancestor both of the Physica et Mystica and of the ordinary artist's recipe book. The techniques were ancient. Archaeology has revealed metal objects inlaid with colors obtained by grinding metals with sulfur, and Homer's description (8th century BC) of the shield of Achilles gives the impression that the artist in his time was virtually able to paint in metal. Democritus is praised by most of the other authors in the Venice-Paris manuscript, and he is much commented upon.

Zosimos

In about 300 A.D., Zosimos provided one of the first definitions of alchemy:

-

Alchemy (330) Ð the study of the composition of waters, movement,

growth, embodying and disembodying, drawing the spirits from bodies and

bonding the spirits within bodies.

Arabic translations of texts by Zosimos were discovered in 1995 in a copy of the book Keys of Mercy and Secrets of Wisdom by Ibn Al-Hassan Ibn Ali Al-Tughra'i', a Persian alchemist. Unfortunately, the translations were incomplete and seemingly non-verbatim.

The famous index of Arabic books, Kitab al-Fihrist by Ibn Al-Nadim, mentions earlier translations of four books by Zosimos, however due to inconsistency in transliteration, these texts were attributed to names "Thosimos", "Dosimos" and "Rimos"; also it is possible that two of them are translations of the same book.

In general, his understanding of alchemy reflects the influence of Hermetic and Sethian-Gnostic spiritualities. The external processes of metallic transmutation the transformations of lead and copper into silver and gold--mirror an inner purification and redemption.

The alchemical vessel is imagined as a baptismal font, and the tincturing vapours of mercury and sulphur are likened to the purifying waters of baptism, which perfect and redeem the Gnostic initiate. Here Zosimos draws on the Hermetic image of the 'krater' or mixing bowl, a symbol of the divine mind in which the Hermetic initiate was 'baptised' and purified in the course of a visionary ascent through the heavens and into the transcendent realms. Similar ideas of a spiritual baptism in the 'waters' of the transcendent Pleroma are characteristic of the Sethian-Gnostic texts unearthed at Nag Hammadi. This image of the alchemical vessel as baptismal font is central to his so-called 'Visions', discussed below.

Zosimos shows what had become of alchemy after Bolos of Mende. His theory is luxuriant in imagery, beginning with a discussion of "the composition of waters, movement, growth, embodying and disembodying, drawing the spirits from bodies and binding the spirits within bodies" and continuing in the same vein. The "base" metals are to be "ennobled" (to gold) by killing and resurrecting them, but his practice is full of distillation and sublimation, and he is obsessed with "spirits." Theory and practice are joined in the concept that success depends upon the production of a series of colours, usually black, white, yellow, and purple, and that the colors are to be obtained through Theion hydor (divine or sulfur water--it could mean either).

Zosimos credits these innovations mainly to Maria (sometimes called "the Jewess"), who invented the apparatus, and to Agathodaimon, probably a pseudonym. Neither is represented (beyond Zosimos' references) in the Venice-Paris manuscript, but a tract attributed to Agathodaimon, published in 1953, shows him to be preoccupied with the colour sequence and complicating it by using arsenic instead of sulfur. Thus, the color-producing potentialities of chemistry were considerable by the time of Zosimos.

The Philosopher's Stone

It was sometimes called a medicine for the rectification of "base" or "sick" metals, and from this it was a short step to view it as a drug for the rectification of human maladies. Zosimos notes the possibility, in passing. When the objective of alchemy became human salvation, the material constitution of the elixir became less important than the incantations that accompanied its production. Synesius, the last author in the Venice-Paris manuscript, already defined alchemy as a mental operation, independent of the science of matter.

Thus, Greek alchemy came to resemble, in both theory and practice, that of China and India.

But its objectives included gold making; thus it remained fundamentally different.

Arabic Alchemy

The Emerald Tablets of Thoth

(He was Hermes)

(As is Above, So is Below)

Zero Point Merge

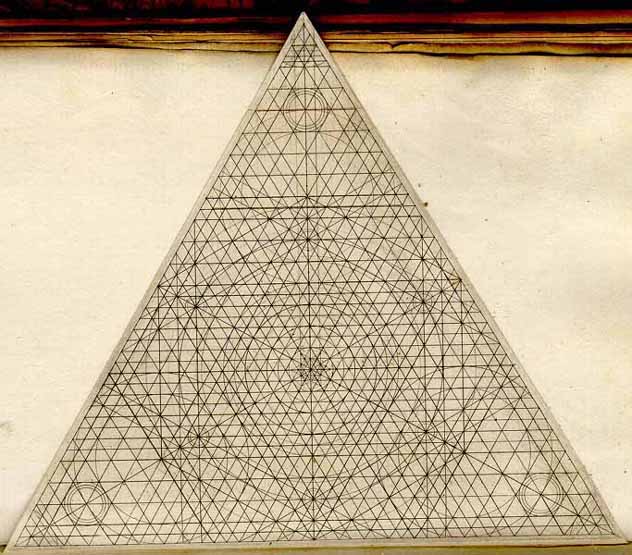

Sacred Geometry - Golden Ratio

Reality as a Consciousness Hologram

Beginning "That which is above is like to that which is below,

and that which is below is like to that which is above,"

it is brief, theoretical, and astrological.

Hermes

Hermes "the thrice great" (Trismegistos) was a Greek version of the Egyptian god Thoth and the supposed founder of an astrological philosophy that is first noted in 150 BC. The Emerald Tablet, however, comes from a larger work called Book of the Secret of Creation, which exists in Latin and Arabic manuscripts and was thought by the Muslim alchemist ar-Razi to have been written during the reign of Caliph al-Ma'mun (AD 813-833), though it has been attributed to the 1st-century-AD pagan mystic Apollonius of Tyana.

Some scholars have suggested that Arabic alchemy descended from a western Asiatic school and that Greek alchemy was derived from an Egyptian school. As far as is known, the Asiatic school was not Chinese or Indian. What is known is that Arabic alchemy was associated with a specific city in Syria, Harran, which seems to have been a fountainhead of alchemical notions. And it is possible that the distillation ideology and its spokeswoman, Maria--as well as Agathodaimon--represented the alchemy of Harran, which presumably migrated to Alexandria and was incorporated into the alchemy of Zosimos.

The existing versions of the Book of the Secret of Creation have been carried back only to the 7th or 6th century but are believed by some to represent much earlier writings, although not necessarily those of Apollonius himself. He is the subject of an ancient biography that says nothing about alchemy, but neither does the Emerald Tablet nor the rest of the Book of the Secret of Creation. On the other hand, their theories of nature have an alchemical ring, and the Book mentions the characteristic materials of alchemy, including, for the first time in the West, sal ammoniac. It was clearly an important book to the Arabs, most of whose eminent philosophers mentioned alchemy, although sometimes disapprovingly.

Those who practiced it were even more interested in literal gold making than had been the Greeks. The most well-attested and probably the greatest Arabic alchemist was ar-Razi (c. 850-923/924), a Persian physician who lived in Baghdad. The most famous was Jabir ibn Hayyan, now believed to be a name applied to a collection of "underground writings" produced in Baghdad after the theological reaction against science. In any case, the Jabirian writings are very similar to those of ar-Razi.

Ar-Razi classified the materials used by the alchemist into "bodies" (the metals), stones, vitriols, boraxes, salts, and "spirits," putting into the latter those vital (and sublimable) materials, mercury, sulfur, orpiment and realgar (the arsenic sulfides), and sal ammoniac. Much is made of sal ammoniac, the reactive powers of which seem to have given Western alchemy a new lease on life. Ar-Razi and the Jabirian writers were really trying to make gold, through the catalytic action of the elixir. Both wrote much on the compounding of "strong waters," an enterprise that was ultimately to lead to the discovery of the mineral acids, but students have been no more able to find evidence of this discovery in the writings of the Arabic alchemists than in those of China and India. The Arabic strong waters were merely corrosive salt solutions.

Ar-Razi's writing represents the apogee of Arabic alchemy, so much so that students of alchemy have little evidence of its later reorientation toward mystical or quasi-religious objectives. Nor does it seem to have turned to medicine, which remained independent. But there was a tendency in Arabic medicine to give greater emphasis to mineral remedies and less to the herbs that had been the chief medicines of the earlier Greek and Arabic physicians. The result was a pharmacopoeia not of elixirs but of specific remedies that are inorganic in origin and not very different from the elixirs of ar-Razi. This new pharmacopoeia was taken to Europe by Constantine of Africa, a Baghdad-educated Muslim who died in 1087 as a Christian monk at Monte Cassino (Italy). The pharmacopoeia also appeared in Spain in the 11th century and passed from there to Latin Europe, along with the Arabic alchemical writings, which were translated into Latin in the 12th century.

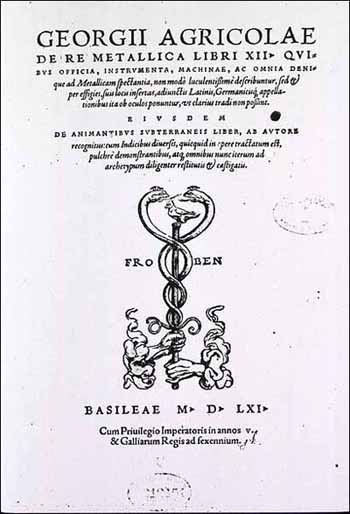

Latin Alchemy

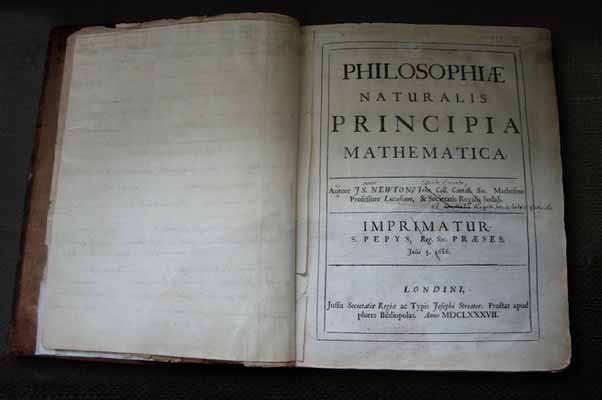

The Greek alchemy of the Venice-Paris manuscript had much less impact than the work of ar-Razi and other Arabs, which emerged among the voluminous translations made in Spain about 1150 by Gerard of Cremona. By 1250 alchemy was familiar enough to enable such encyclopaedists as Vincent of Beauvais to discuss it fairly intelligibly, and before 1300 the subject was under discussion by the English philosopher and scientist Roger Bacon and the German philosopher, scientist, and theologian Albertus Magnus.

To learn about alchemy was to learn about chemistry, for Europe had no independent word to describe the science of matter. It had been touched upon in works concerned with other forms of change--e.g., the motion of projectiles, the aging of man, and similar Aristotelian concepts. On the practical side there were also artists' recipe books; but for the first time in the works of Bacon and Albertus Magnus change was discussed in a truly chemical sense, with Bacon treating the newly translated alchemy as a general science of matter for which he had great hopes.

But the more familiar alchemy became, the more clearly it was understood that gold making was the almost exclusive objective of alchemy, and Europeans proved no more resistant to the lure of this objective than their Arabic predecessors. By 1350, alchemical tracts were pouring out of the scriptoria (monastic copying rooms), and the Europeans had even taken over the tradition of anonymity and false attribution.

One authority wrote at length about supposed disagreements between two Arabs, Iahiae Abindinon and Geber Abinhaen, who were probably two versions of the name of Jabir ibn Hayyan. The most famous Jabirian work in Europe, The Sum of Perfection, is now thought to have been an original European composition. At about this time personal reminiscences of alchemists began to appear.

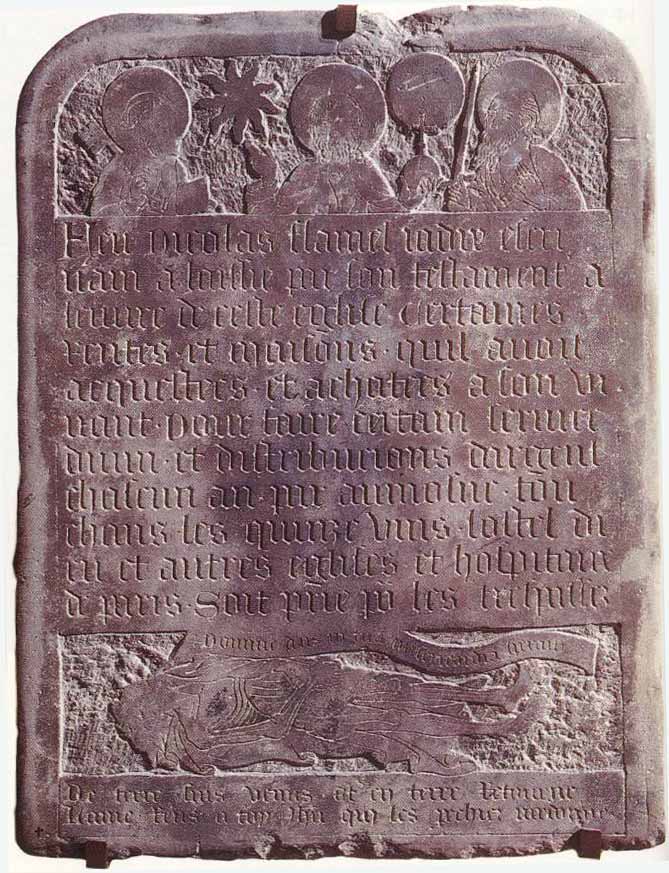

Most famous was the Paris notary Nicolas Flamel (1330-1418), who claimed that he dreamed of an occult book, subsequently found it, and succeeded in deciphering it with the aid of a Jewish scholar learned in the mystic Hebrew writings known as the Kabbala. In 1382 Flamel claimed to have succeeded in the "Great Work" (gold making); certainly he became rich and made donations to churches.

By 1300 alchemists had begun the discovery of the mineral acids, a discovery that occupied about three centuries between the first evidence of the new strong water (aqua fortis--i.e., nitric acid) and the clear differentiation of the acids into three kinds: nitric, hydrochloric, and sulfuric. These three centuries saw prodigious efforts in European alchemy, for these spontaneously reactive and highly corrosive substances opened a whole new world of research. And yet, it was of little profit to chemistry, for the experiments were inhibited by the old objectives of separating the base metals into their "elements," concocting elixirs, and other traditional procedures.

The "water of life" (aqua vitae; i.e., alcohol) was probably discovered a little earlier than nitric acid, and some physicians and a few alchemists turned to the elixir of life as an objective. John of Rupescissa, a Catalonian monk who wrote c. 1350, prescribed virtually the same elixirs for metal ennoblement and for the preservation of health. His successors multiplied elixirs, which lost their uniqueness and finally simply became new medicines, often for specific ailments.

Medical chemistry may have been conceived under Islam, but it was born in Europe. It only awaited christening by its great publicist, Paracelsus (1493-1541), who was the sworn enemy of the malpractices of 16th-century medicine and a vigorous advocate of "folk" and "chemical" remedies. By the end of the 16th century, medicine was divided into warring camps of Paracelsians and anti-Paracelsians, and the alchemists began to move en masse into pharmacy.

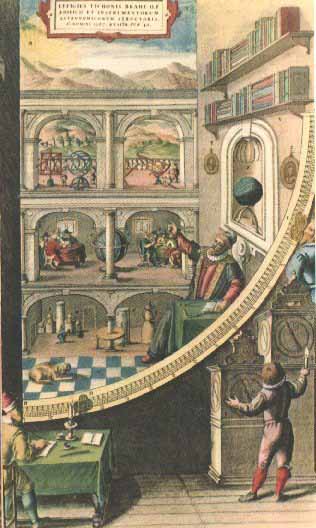

Paracelsian pharmacy was to lead, by a devious path, to modern chemistry, but gold making still persisted, though methods sometimes differed. SalomonTrismosin, purported author of the Splendor solis, or "Splendour of the Sun" (published 1598), engaged in extensive visits to alchemical adepts (a common practice) and claimed success through "kabbalistic and magical books in the Egyptian language." The impression given is that many had the secret of gold making but that most of them had acquired it from someone else and not from personal experimentation. Illustrations, often heavily symbolic, became particularly important, those of Splendor solis being far more complex than the text but clearly exercising a greater appeal, even to modern students.

Modern Alchemy

This was not altogether to the alchemist's advantage. In 1595 Edward Kelley, an English alchemist and companion of the famous astrologer, alchemist, and mathematician John Dee, lost his life in an attempt to escape after imprisonment by Rudolf II, and in 1603 the elector of Saxony, Christian II, imprisoned and tortured the Scotsman Alexander Seton, who had been traveling about Europe performing well-publicized transmutations.

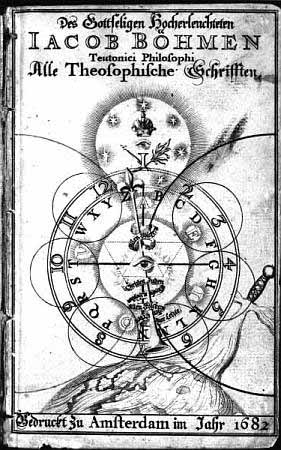

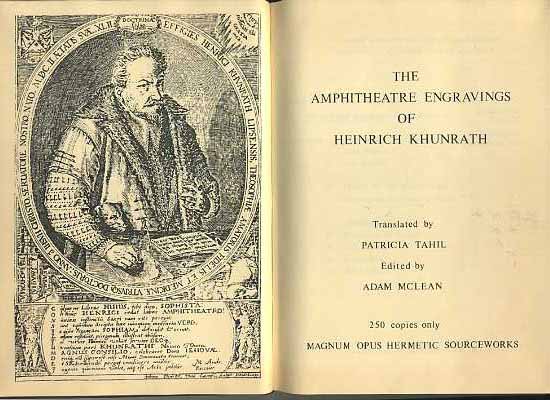

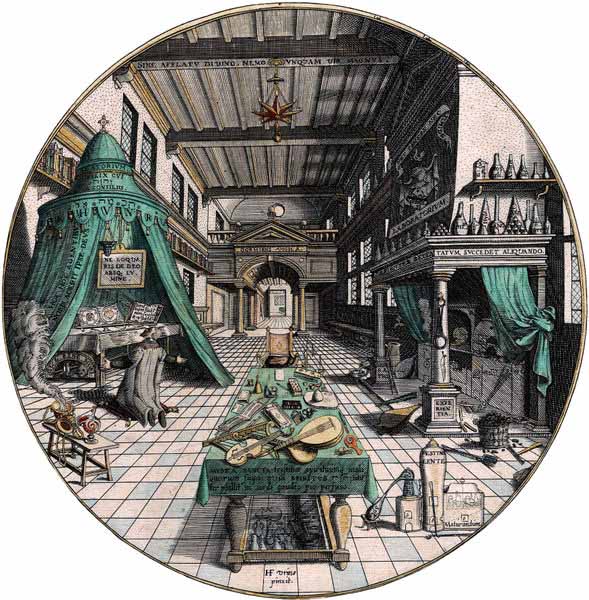

The situation was complicated by the fact that some alchemists were turning from gold making not to medicine but to a quasi-religious alchemy reminiscent of the Greek Synesius. Rudolf II made the German alchemist Michael Maier a count and his private secretary, although Maier's mystical and allegorical writings were, in the words of a modern authority, "distinguished for the extraordinary obscurity of his style" and made no claim to gold making. Neither did the German alchemist Heinrich Khunrath (c. 1560-1601), whose works have long been esteemed for their illustrations, make such a claim.

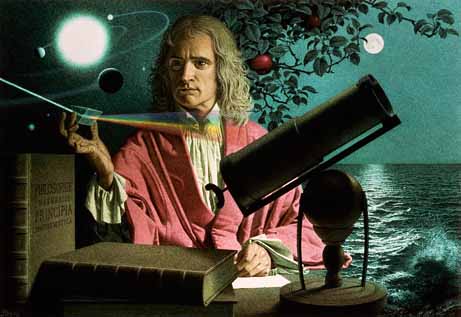

Conventional attempts at gold making were not dead, but by the 18th century alchemy had turned conclusively to religious aims. The rise of modern chemistry engendered not only general skepticism as to the possibility of making gold but also widespread dissatisfaction with the objectives of modern science, which were viewed as too limited.

Unlike the scientists of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, the successors of Newton and the great 18th-century French chemist Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier limited their objectives in a way that amounted to a renunciation of what many had considered the most important question of science, the relation of man to the cosmos. Those who persisted in asking these questions came to feel an affinity with the alchemists and sought their answers in the texts of "esoteric," or spiritual, alchemy (as distinct from the "exoteric" alchemy of the gold makers), with its roots in Synesius and other late Greek alchemists of the Venice-Paris manuscript.

This spiritual alchemy, or Hermetism, as its practitioners often prefer to call it, was popularly associated with the supposititious Rosicrucian brotherhood, whose so-called Manifestoes (author unknown; popularly ascribed to the German theologian Johann Valentin AndreŠ) had appeared in Germany in the early 17th century and had attracted the favorable attention not only of such reforming alchemists as Michael Maier but also of many prominent philosophers who were disquieted by the mechanistic character of the new science.

In modern times alchemy has become a focal point for various kinds of mysticism. The old alchemical literature continues to be scrutinized for evidence, because alchemical doctrine is claimed to have on more than one occasion come into the possession of man but always again been lost. Nor is its association with chemistry considered accidental.

In the words of the famous 19th-century English spiritual alchemist Mary Anne Atwood,

- Alchemy is an universal art of vital chemistry which by fermenting the human spirit

purifies and finally dissolves it. . . . Alchemy is philosophy; it is the philosophy, the

finding of the Sophia in the mind.

Assessments of Alchemy

It has been said that alchemy can be credited with the development of the science of chemistry, a keystone of modern science. During the alchemical period the repertoire of known substances was enlarged (e.g., by the addition of sal ammoniac and saltpetre), alcohol and the mineral acids were discovered, and the basis was laid from which modern chemistry was to rise.

Historians of chemistry have been tempted to credit alchemy with laying this base while at the same time regarding alchemy as mostly "wrong." It is far from clear, however, that the basis of chemistry was in fact laid by alchemy rather than medicine. During the crucial period of Arabic and early Latin alchemy, it appears that innovation owed more to nascent medical chemistry than to alchemy.

But those who explore the history of the science of matter, where matter is considered on a wider basis than the modern chemist understands the term, may find alchemy more rewarding.

Numerous Hermetic writers of previous centuries claimed that the aims of their art could yet be achieved--indeed, that the true knowledge had been repeatedly found and repeatedly lost. This is a matter of judgment, but it can certainly be said that the modern chemist has not attained the goal sought by the alchemist. For those who are wedded to scientific chemistry, alchemy can have no further interest. For those who seek the wider goal, which was also that of the natural philosopher before the advent of "mechanical," "Newtonian," or "modern" science, the search is still on.

Interpretations

Other historians of chemistry have attempted to differentiate the good from the bad in alchemy, citing as good the discovery of new substances and processes and the invention of new apparatus. Some of this was certainly accomplished by alchemists (e.g., Maria), but most of it is more justifiably ascribed to early pharmacists.

Scholars generally agree that alchemy had something to do with chemistry, but the modern Hermetic holds that chemistry was the handmaiden of alchemy, not the reverse. From this point of view the development of modern chemistry involved the abandonment of the true goal of the art.

Finally, a new interpretation was offered in the 1920s by the Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung, who, following the earlier work of the Austrian psychologist Herbert Silberer, judged alchemical literature to be explicable in psychological terms. Noticing the similarities between alchemical literature, particularly in its reliance on bizarre symbolic illustrations, and the dreams and fantasies of his patients, Jung viewed them as manifestations of a "collective unconscious" (inherited disposition). Jung's theory, still largely undeveloped, remains a challenge rather than an explanation.

\

\

Alchemy was the precursor to modern chemistry. Alchemists were therefore chemists, pharmacologists, and physicians. Alchemy flourished in the Islamic world during the Middle Ages, and then in Europe from the 13th to the 18th centuries. We know the names of some of the better known alchemists thanks to the numerous alchemical manuscript and books that survived. It must be kept in mind however that the vast majority of ancient alchemists, being self-taught, and more bent on experimenting than writing, have left no trace in history.

Middle East

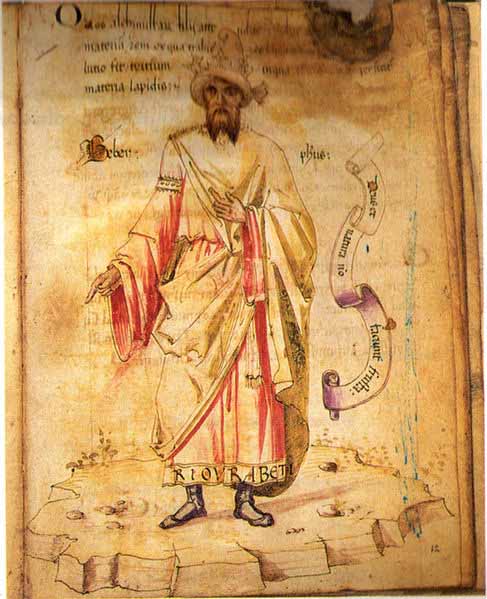

Geber

Geber, aka Abu Musa Jabir ibn Hayyan, was a prominent Islamic alchemist, pharmacist, philosopher, astronomer, and physicist. He has also been referred to as "the father of Arab chemistry" by Europeans. His ethnic background is not clear; although most sources state he was an Arab, some describe him as Persian.

Jabir was born in Tus, Khorasan, in Iran, which was at the time ruled by the Umayyad Caliphate; the date of his birth is disputed, but most sources give 721 or 722. He was the son of Hayyan al-Azdi, a pharmacist of the Arabian Azd tribe who emigrated from Yemen to Kufa (in present-day Iraq) during the Umayyad Caliphate.

Hayyan had supported the revolting Abbasids against the Umayyads, and was sent by them to the province of Khorasan (in present Iran) to gather support for their cause. He was eventually caught by the Ummayads and executed. His family fled back to Yemen, where Jabir grew up and studied the Koran, mathematics and other subjects under a scholar named Harbi al-Himyari.

After the Abbasids took power, Jabir went back to Kufa, where he spent most of his career. Jabir's father's profession may have contributed greatly to his interest to chemistry.

In Kufa he became a student of the celebrated Islamic teacher and sixth Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq.

It is said that he also studied with the Umayyad prince Khalid Ibn Yazid. He began his career

practising medicine, under the patronage of the Barmakid Vizir of Caliph Haroun al-Rashid.

It is known that in 776 he was engaged in alchemy in Kufa.His connections to the Barmakid cost him dearly in the end. When that family fell from grace in 803, Jabir was placed under house arrest in Kufa, where he remained until his death.

The date of his death is given as c.815 by the Encyclop¾dia Britannica, but as 808 by other sources.

Contributions to Chemistry

He also paved the way for most of the later Islamic alchemists, including al-Razi, al-Tughrai and al-Iraqi, who lived in the 9th, 12th and 13th centuries respectively. His books strongly influenced the medieval European alchemists and justified their search for the philosopher's stone.In spite of his leanings toward mysticism (he was considered a Sufi) and superstition, he more clearly recognised and proclaimed the importance of experimentation.

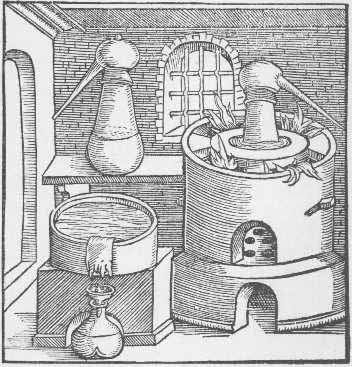

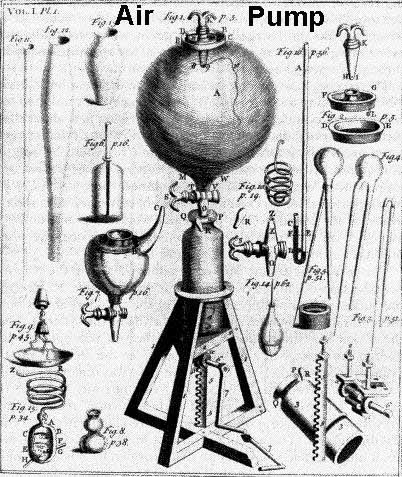

"The first essential in chemistry", he declared, "is that you should perform practical work and conduct experiments, for he who performs not practical work nor makes experiments will never attain the least degree of mastery."Jabir is also credited with the invention and development of several chemical instruments that are still used today, such as the alembic, which made distillation easy, safe, and efficient.

Distillation Process

Jabir applied his chemical knowledge to the improvement of many manufacturing processes, such as making steel and other metals, preventing rust, engraving gold, dyeing and waterproofing cloth, tanning leather, and the chemical analysis of pigments and other substances. He developed the use of manganese dioxide in glassmaking, to counteract the green tinge produced by iron - a process that is still used today. He noted that boiling wine released a flammable vapor, thus paving the way to Al-Razi's discovery of ethanol.

The seeds of the modern classification of elements into metals and non-metals could be seen in his chemical nomenclature. He proposed three categories: "spirits" which vaporise on heating, like camphor, arsenic, and ammonium chloride; "metals", like gold, silver, lead, copper, and iron; and "stones" that can be converted into powders.In the Middle Ages, Jabir's treatises on chemistry were translated into Latin and became standard texts for European alchemists.

These include the Kitab al-Kimya (titled Book of the Composition of Alchemy in Europe), translated by Robert of Chester (1144); and the Kitab al-Sab'een by Gerard of Cremona (before 1187). Marcelin Berthelot translated some of his books under the fanciful titles Book of the Kingdom, Book of the Balances, and Book of Eastern Mercury.

Several technical terms introduced by Jabir, such as alkali, have found their way into various European languages and have become part of scientific vocabulary.

Contributions to Alchemy

Jabir's alchemical investigations revolved around the ultimate goal of takwin - the artificial creation of life. Alchemy had a long relationship with Shi'ite mysticism; according to the first Imam, Ali ibn Abi Talib, "alchemy is the sister of prophecy".

Jabir's interest in alchemy was probably inspired by his teacher Ja'far al-Sadiq, and he was himself called "the Sufi", indicating that he followed the ascetic form of mysticism within Islam.In his writings, Jabir pays tribute to Egyptian and Greek alchemists Hermes Trismegistus, Agathodaimon, Pythagoras, and Socrates.

He emphasises the long history of alchemy, "whose origin is Arius ... the first man who applied the first experiment on the [philosopher's] stone... and he declares that man possesses the ability to imitate the workings of Nature" (Nasr, Seyyed Hossein, Science and Civilization of Islam).

Jabir states in his Book of Stones (4:12) that "The purpose is to baffle and lead into error everyone except those whom God loves and provides for". His works seem to have been deliberately written in highly esoteric code, so that only those who had been initiated into his alchemical school could understand them. It is therefore difficult at best for the modern reader to discern which aspects of Jabir's work are to be read as symbols (and what those symbols mean), and what is to be taken literally. Because his works rarely made overt sense, the term gibberish is believed to have originally referred to his writings (Hauck, p. 19).

Jabir's alchemical investigations were theoretically grounded in an elaborate numerology related to Pythagorean and Neoplatonic systems. The nature and properties of elements was defined through numeric values assigned the Arabic consonants present in their name, ultimately culminating in the number 17.

To Aristotelian physics, Jabir added the four properties of hotness, coldness, dryness, and moistness (Burkhardt, p. 29). Each Aristotelian element was characterised by these qualities: Fire was both hot and dry, earth cold and dry, water cold and moist, and air hot and moist. This came from the elementary qualities which are theoretical in nature plus substance. In metals two of these qualities were interior and two were exterior. For example, lead was cold and dry and gold was hot and moist.

Thus, Jabir theorised, by rearranging the qualities of one metal, based on their sulfur/mercury content, a different metal would result. (Burckhardt, p. 29) This theory appears to have originated the search for al-iksir, the elusive elixir that would make this transformation possible - which in European alchemy became known as the philosopher's stone.

Jabir also made important contributions to medicine, astronomy, and other sciences. Only a few of his books have been edited and published, and fewer still are available in translation. The Geber crater, located on the Moon, is named after him.

Writings by Jabir

- The 112 Books dedicated to the Barmakids, viziers of Caliph Harun al-Rashid. This group includes the Arabic version of the Emerald Tablet, an ancient work that is the foundation of the Hermetic or "spiritual" alchemy. In the Middle Ages it was translated into Latin (Tabula Smaragdina) and widely diffused among European alchemists.

- The Seventy Books, most of which were translated into Latin during the Middle Ages. This group includes the Kitab al-Zuhra ("Book of Venus") and the Kitab Al-Ahjar ("Book of Stones").

- The Ten Books on Rectification, containing descriptions of "alchemists" such as Pythagoras, Socrates, Plato and Aristotle.

- The Books on Balance; this group includes his most famous 'Theory of the balance in Nature'.Some scholars suspect that some of these works were not written by Jabir himself, but are instead commentaries and additions by his followers. In any case, they all can be considered works of the 'Jabir' school of alchemy.

Mohammad Ibn Zakariya al-Razi

Muhammad ibn Zakariya Razi known as Rhazes or Rasis after medieval Latinists, (August 26, 865-925) was a Persian polymath, a prominent figure in Islamic Golden Age, physician, alchemist and chemist, philosopher, and scholar

Numerous ÒfirstsÓ in medical research, clinical care, and chemistry are attributed to him, including being the first to differentiate smallpox from measles, and the discovery of numerous compounds and chemicals including kerosene, among others. Edward Granville Browne considers him as "probably the greatest and most original of all the physicians, and one of the most prolific as an author".

Razi made fundamental and enduring contributions to the fields of medicine, alchemy, music, and philosophy, recorded in over 200 books and articles in various fields of science. He was well-versed in Persian, Greek and Indian medical knowledge and made numerous advances in medicine through own observations and discoveries.

Educated in music, mathematics, philosophy, and metaphysics, he chose medicine as his professional field. As a physician, he was an early proponent of experimental medicine and has been described as the father of pediatrics. He was also a pioneer of ophthalmology. He was among the first to use Humoralism to distinguish one contagious disease from another. In particular, Razi was the first physician to distinguish smallpox and measles through his clinical characterization of the two diseases. He became chief physician of Rey and Baghdad hospitals.

As an alchemist, Razi is known for his study of sulfuric acid. He traveled extensively, mostly in Persia. As a teacher in medicine, he attracted students of all disciplines and was said to be compassionate and devoted to the service of his patients, whether rich or poor.

Life and Background

There is a difference of opinion as to whether he was an Arab from Kufa who lived in Khurasan or a Persian from Khorasan who later went to Kufa or whether he was, as some have suggested, of Syrian origin and later lived in Persia and Iraq. His ethnic background is not clear,and sources reference him as an Arab or a Persian.

In some sources, he is reported to have been the son of Hayyan al-Azdi, a pharmacist of the Arabian Azd tribe who emigrated from Yemen to Kufa (in present-day Iraq) during the Umayyad Caliphate. while Henry Corbin believes Geber seems to have been a client of the 'Azd tribe. Jabir became an alchemist at the court of Caliph Harun al-Rashid, for whom he wrote the Kitab al-Zuhra ("The Book of Venus", on "the noble art of alchemy"). Hayyan had supported the Abbasid revolt against the Umayyads, and was sent by them to the province of Khorasan (present day Afghanistan and Iran) to gather support for their cause. He was eventually caught by the Ummayads and executed. His family fled to Yemen, where Jabir grew up and studied the Quran, mathematics and other subjects.Jabir's father's profession may have contributed greatly to his interest in alchemy.

After the Abbasids took power, Jabir went back to Kufa. He began his career practicing medicine, under the patronage of a Vizir (from the noble Persian family Barmakids) of Caliph Harun al-Rashid. His connections to the Barmakid cost him dearly in the end. When that family fell from grace in 803, Jabir was placed under house arrest in Kufa, where he remained until his death.

It has been asserted that Jabir was a student of the sixth Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq and Harbi al-Himyari, however other scholars have questioned this theory.

Razi wrote 184 books and articles, in several fields of science. His books and articles are named by Ibn Abi Asi'boed.

Ibn an-Nadim identifies five areas in which Razi distinguished himself:

- 1. Razi was recognized as the best physician of his time who had fully absorbed Greek

medical learning.

2. He traveled in many lands. His repeated visits to Baghdad and his services to many princes and rulers are known from many sources.

3. He was a medical educator who attracted many students, both beginners and advanced.

4. He was compassionate, kind, upright, and devoted to the service of his patients whether rich or poor.

5. He was a prolific reader and writer and authored many books.

Avicenna

Avicenna, aka Abu Ali al-Husain ibn Abdallah ibn Sina, was a Persian polymath, physician, philosopher, and scientist who wrote almost 450 treatises on a wide range of subjects, of which around 240 have survived. Many of his woorks concentrated on philosophy and medicine. He is considered by many to be "the father of modern medicine." In particular, 150 of his surviving treatises concentrate on philosophy and 40 of them concentrate on medicine.

His most famous works are The Book of Healing, a vast philosophical and scientific encyclopedia, and The Canon of Medicine, which was a standard medical text at many medieval universities. The Canon of Medicine was used as a text-book in the universities of Montpellier and Leuven as late as 1650. Ibn Sina's Canon of Medicine provides a complete system of medicine according to the principles of Galen (and Hippocrates).

His corpus also includes writing on philosophy, astronomy, alchemy, geology, psychology, Islamic theology, logic, mathematics, physics, as well as poetry. He is regarded as the most famous and influential polymath of the Islamic Golden Age.

Avicenna created an extensive corpus of works during what is commonly known as Islam's Golden Age, in which the translations of Greco-Roman, Persian, and Indian texts were studied extensively. Greco-Roman (Mid- and Neo-Platonic, and Aristotelian) texts by the Kindi school were commented, redacted and developed substantially by Islamic intellectuals, who also built upon Persian and Indian mathematical systems, astronomy, algebra, trigonometry and medicine. The Samanid dynasty in the eastern part of Persia, Greater Khorasan and Central Asia as well as the Buyid dynasty in the western part of Persia and Iraq provided a thriving atmosphere for scholarly and cultural development. Under the Samanids, Bukhara rivaled Baghdad as a cultural capital of the Islamic world.

The study of the Quran and the Hadith thrived in such a scholarly atmosphere. Philosophy, Fiqh and theology (kalaam) were further developed, most noticeably by Avicenna and his opponents. Al-Razi and Al-Farabi had provided methodology and knowledge in medicine and philosophy. Avicenna had access to the great libraries of Balkh, Khwarezm, Gorgan, Rey, Isfahan and Hamadan. Various texts (such as the 'Ahd with Bahmanyar) show that he debated philosophical points with the greatest scholars of the time. Aruzi Samarqandi describes how before Avicenna left Khwarezm he had met Abu Rayhan Biruni (a famous scientist and astronomer), Abu Nasr Iraqi (a renowned mathematician), Abu Sahl Masihi (a respected philosopher) and Abu al-Khayr Khammar (a great physician).

Early Life

Avicenna was born c. 980 near Bukhara (in present-day Uzbekistan), the capital of the Samanids, a Persian dynasty in Central Asia and Greater Khorasan. His mother, named Setareh, was from Bukhara; his father, Abdullah, was a respected Ismaili scholar from Balkh, an important town of the Samanid Empire, in what is today Balkh Province, Afghanistan. His father was at the time of his son's birth the governor in one of the Samanid Nuh ibn Mansur's estates. He had his son very carefully educated at Bukhara. Ibn Sina's independent thought was served by an extraordinary intelligence and memory, which allowed him to overtake his teachers at the age of fourteen. As he said in his autobiography, there was nothing that he had not learned when he reached eighteen.

A number of different theories have been proposed regarding Avicenna's madhab. Medieval historian Zahir al-din al-Bayhaqi (d. 1169) considered Avicenna to be a follower of the Brethren of Purity. On the other hands, Shia faqih Nurullah Shushtari and Seyyed Hossein Nasr, in addition to Henry Corbin, have maintained that he was most likely a Twelver Shia. More recently, however, Dimitri Gutas demonstrated that Avicenna was a Sunni Hanafi. Similar disagreements exist on the background of Avicenna's family, whereas some writers considered them Sunni, more recent writers thought they were Shia.

According to his autobiography, Avicenna had memorized the entire Qur'an by the age of 10. He learned Indian arithmetic from an Indian greengrocer, and he began to learn more from a wandering scholar who gained a livelihood by curing the sick and teaching the young. He also studied Fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence) under the Hanafi scholar Ismail al-Zahid.

As a teenager, he was greatly troubled by the Metaphysics of Aristotle, which he could not understand until he read al-Farabi's commentary on the work. For the next year and a half, he studied philosophy, in which he encountered greater obstacles. In such moments of baffled inquiry, he would leave his books, perform the requisite ablutions (wudu), then go to the mosque, and continue in prayer (salah) till light broke on his difficulties.

Deep into the night, he would continue his studies, and even in his dreams problems would pursue him and work out their solution. Forty times, it is said, he read through the Metaphysics of Aristotle, till the words were imprinted on his memory; but their meaning was hopelessly obscure, until one day they found illumination, from the little commentary by Farabi, which he bought at a bookstall for the small sum of three dirhams. So great was his joy at the discovery, made with the help of a work from which he had expected only mystery, that he hastened to return thanks to God, and bestowed alms upon the poor.

He turned to medicine at 16, and not only learned medical theory, but also by gratuitous attendance of the sick had, according to his own account, discovered new methods of treatment. The teenager achieved full status as a qualified physician at age 18 and found that "Medicine is no hard and thorny science, like mathematics and metaphysics, so I soon made great progress; I became an excellent doctor and began to treat patients, using approved remedies." The youthful physician's fame spread quickly, and he treated many patients without asking for payment.

Adulthood

Avecenna 1271

When Ibn Sina was 22 years old, he lost his father. The Samanid dynasty came to its end in December 1004. Ibn Sina seems to have declined the offers of Mahmud of Ghazni, and proceeded westwards to Urgench in modern Turkmenistan, where the vizier, regarded as a friend of scholars, gave him a small monthly stipend. The pay was small, however, so Ibn Sina wandered from place to place through the districts of Nishapur and Merv to the borders of Khorasan, seeking an opening for his talents.

Qabus, the generous ruler of Dailam and central Persia, himself a poet and a scholar, with whom Ibn Sina had expected to find asylum, was on about that date (1012) starved to death by his troops who had revolted. Ibn Sina himself was at this time stricken by a severe illness. Finally, at Gorgan, near the Caspian Sea, Ibn Sina met with a friend, who bought a dwelling near his own house in which Ibn Sina lectured on logic and astronomy. Several of Ibn Sina's treatises were written for this patron; and the commencement of his Canon of Medicine also dates from his stay in Hyrcania.

Ibn Sina subsequently settled at Rai, in the vicinity of modern Tehran, (present day capital of Iran), the home town of Rhazes; where Majd Addaula, a son of the last Buwayhid emir, was nominal ruler under the regency of his mother (Seyyedeh Khatun). About thirty of Ibn Sina's shorter works are said to have been composed in Rai. Constant feuds which raged between the regent and her second son, Shams al-Daula, however, compelled the scholar to quit the place. After a brief sojourn at Qazvin he passed southwards to Hamadan where Shams al-Daula, another Buwayhid emir, had established himself.

At first, Ibn Sina entered into the service of a high-born lady; but the emir, hearing of his arrival, called him in as medical attendant, and sent him back with presents to his dwelling. Ibn Sina was even raised to the office of vizier. The emir decreed that he should be banished from the country.

Ibn Sina, however, remained hidden for forty days in sheikh Ahmed Fadhel's house, until a fresh attack of illness induced the emir to restore him to his post. Even during this perturbed time, Ibn Sina persevered with his studies and teaching. Every evening, extracts from his great works, the Canon and the Sanatio, were dictated and explained to his pupils. On the death of the emir, Ibn Sina ceased to be vizier and hid himself in the house of an apothecary, where, with intense assiduity, he continued the composition of his works.

Meanwhile, he had written to Abu Ya'far, the prefect of the dynamic city of Isfahan, offering his services. The new emir of Hamadan, hearing of this correspondence and discovering where Ibn Sina was hiding, incarcerated him in a fortress. War meanwhile continued between the rulers of Isfahan and Hamadan; in 1024 the former captured Hamadan and its towns, expelling the Tajik mercenaries. When the storm had passed, Ibn Sina returned with the emir to Hamadan, and carried on his literary labors. Later, however, accompanied by his brother, a favorite pupil, and two slaves, Ibn Sina escaped from the city in the dress of a Sufi ascetic. After a perilous journey, they reached Isfahan, receiving an honorable welcome from the prince.

Later Life and Death

Avicenna Mausoleum

During these years he began to study literary matters and philology, instigated, it is asserted, by criticisms on his style. A severe colic, which seized him on the march of the army against Hamadan, was checked by remedies so violent that Ibn Sina could scarcely stand. On a similar occasion the disease returned; with difficulty he reached Hamadan, where, finding the disease gaining ground, he refused to keep up the regimen imposed, and resigned himself to his fate.

His friends advised him to slow down and take life moderately. He refused, however, stating that: "I prefer a short life with width to a narrow one with length". On his deathbed remorse seized him; he bestowed his goods on the poor, restored unjust gains, freed his slaves, and read through the Qur'an every three days until his death. He died in June 1037, in his fifty-eighth year, in the month of Ramadan and was buried in Hamadan, Iran.

Avicennian Philosophy

In the medieval Islamic world, due to Avicenna's successful reconciliation between Aristotelianism and Neoplatonism along with Kalam, Avicennism eventually became the leading school of Islamic philosophy by the 12th century, with Avicenna becoming a central authority on philosophy.

Avicennism was also influential in medieval Europe, particular his doctrines on the nature of the soul and his existence-essence distinction, along with the debates and censure that they raised in scholastic Europe. This was particularly the case in Paris, where Avicennism was later proscribed in 1210. Nevertheless, his psychology and theory of knowledge influenced William of Auvergne, Bishop of Paris and Albertus Magnus, while his metaphysics had an impact on the thought of Thomas Aquinas.

Metaphysical Doctrine

Following al-Farabi's lead, Avicenna initiated a full-fledged inquiry into the question of being, in which he distinguished between essence (Mahiat) and existence (Wujud). He argued that the fact of existence can not be inferred from or accounted for by the essence of existing things, and that form and matter by themselves cannot interact and originate the movement of the universe or the progressive actualization of existing things. Existence must, therefore, be due to an agent-cause that necessitates, imparts, gives, or adds existence to an essence. To do so, the cause must be an existing thing and coexist with its effect.

AvicennaÕs consideration of the essence-attributes question may be elucidated in terms of his ontological analysis of the modalities of being; namely impossibility, contingency, and necessity.

Avicenna argued that the impossible being is that which cannot exist, while the contingent in itself (mumkin bi-dhatihi) has the potentiality to be or not to be without entailing a contradiction. When actualized, the contingent becomes a Ônecessary existent due to what is other than itself' (wajib al-wujud bi-ghayrihi). Thus, contingency-in-itself is potential beingness that could eventually be actualized by an external cause other than itself.

The metaphysical structures of necessity and contingency are different. Necessary being due to itself (wajib al-wujud bi-dhatihi) is true in itself, while the contingent being is 'false in itself' and Ôtrue due to something else other than itselfÕ. The necessary is the source of its own being without borrowed existence. It is what always exists.

The Necessary exists Ôdue-to-Its-SelfÕ, and has no quiddity/essence (mahiyya) other than existence (wujud). Furthermore, It is ÔOneÕ (wahid ahad) since there cannot be more than one ÔNecessary-Existent-due-to-ItselfÕ without differentia (fasl) to distinguish them from each other. Yet, to require differentia entails that they exist Ôdue-to-themselvesÕ as well as Ôdue to what is other than themselvesÕ; and this is contradictory. However, if no differentia distinguishes them from each other, then there is no sense in which these ÔExistentsÕ are not one and the same. Avicenna adds that the 'Necessary-Existent-due-to-Itself' has no genus (jins), nor a definition (hadd), nor a counterpart (nadd), nor an opposite (did), and is detached (bari') from matter (madda), quality (kayf), quantity (kam), place (ayn), situation (wadÕ), and time (waqt).

Ibn Sina memorized the Qur'an by the age of seven, and as an adult, he wrote five treatises commenting on suras from the Qur'an. One of these texts included the Proof of Prophecies, in which he comments on several Quranic verses and holds the Qur'an in high esteem. Avicenna argued that the Islamic prophets should be considered higher than philosophers.

The thought experiment told its readers to imagine themselves created all at once while suspended in the air, isolated from all sensations, which includes no sensory contact with even their own bodies. He argued that, in this scenario, one would still have self-consciousness.

Because it is conceivable that a person, suspended in air while cut off from sense experience, would still be capable of determining his own existence, the thought experiment points to the conclusions that the soul is a perfection, independent of the body, and an immaterial substance. The conceivability of this "Floating Man" indicates that the soul is perceived intellectually, which entails the soulÕs separateness from the body.

Avicenna referred to the living human intelligence, particularly the active intellect, which he believed to be the hypostasis by which God communicates truth to the human mind and imparts order and intelligibility to nature. However, Avicenna posited the brain as the place where reason interacts with sensation. Sensation prepares the soul to receive rational concepts from the universal Agent Intellect.

The first knowledge of the flying person would be "I am," affirming his or her essence. That essence could not be the body, obviously, as the flying person has no sensation. Thus, the knowledge that "I am" is the core of a human being: the soul exists and is self-aware. Avicenna thus concluded that the idea of the self is not logically dependent on any physical thing, and that the soul should not be seen in relative terms, but as a primary given, a substance. The body is unnecessary; in relation to it, the soul is its perfection. In itself, the soul is an immaterial substance.

Legacy

George Sarton, the author of The History of Science, described Ibn Sina as "one of the greatest thinkers and medical scholars in history" and called him "the most famous scientist of Islam and one of the most famous of all races, places, and times." He was one of the Islamic world's leading writers in the field of medicine, and similarly to earlier Islamic writers he followed the approach of Galen (and Hippocrates as transmitted through Galen).

Along with Rhazes, Abulcasis, Ibn al-Nafis, and al-Ibadi, Ibn Sina is considered an important compiler of early Muslim medicine. He is remembered in the Western history of medicine as a major historical figure who made important contributions to medicine and the European Renaissance. His medical texts were unusual in that where controversy existed between Galen and Aristotle's views on medical matters (such as anatomy), he preferred to side with Aristotle, where necessary updating Aristotle's position to take into account post-Aristotilian advances in anatomical knowledge.

Aristotle's dominant intellectual influence among medieval European scholars meant that Avicenna's linking of Galen's medical writings with Aristotle's philosophical writings in the Canon of Medicine (along with its comprehensive and logical organization of knowledge) significantly increased Avicenna's importance in medieval Europe in comparison to other Islamic writers on medicine. His influence following translation of the Canon was such that from the early fourteenth to the mid-sixteenth centuries he was ranked with Hippocrates and Galen as one of the acknowledged authorities, princeps medicorum (prince of physicians).

In Iran, he is considered a national icon, and is often regarded as one of the greatest Persians to have ever lived. Many portraits and statues remain in Iran today. An impressive monument to the life and works of the man who is known as the 'doctor of doctors' still stands outside the Bukhara museum and his portrait hangs in the Hall of the Avicenna Faculty of Medicine in the University of Paris. There is also a crater on the Moon named Avicenna and a plant genus Avicennia.

Bu-Ali Sina University in Hamadan (Iran), the ibn Sina Tajik State Medical University in Dushanbe (The capital of the Republic of Tajikistan), Ibn Sina Academy of Medieval Medicine and Sciences at Aligarh, India, Avicenna School in Karachi and Avicenna Medical College in Lahore Pakistan, Ibne Sina Balkh Medical School in his native province of Balkh in Afghanistan, Ibni Sina Faculty Of Medicine of Ankara University Ankara, Turkey and Ibn Sina Integrated School in Marawi City (Philippines) are all named in his honor.

In 1980, the former Soviet Union, which then ruled his birthplace Bukhara, celebrated the thousandth anniversary of Avicenna's birth by circulating various commemorative stamps with artistic illustrations, and by erecting a bust of Avicenna based on anthropological research by Soviet scholars. Near his birthplace in Qishlak Afshona, some 25 km (16 mi). north of Bukhara, a training college for medical staff has been named for him. On the grounds is a museum dedicated to his life, times and work.

In March 2008, it was announced that Avicenna's name would be used for new Directories of education institutions for health care professionals, worldwide. The Avicenna Directories will list universities and schools where doctors, public health practitioners, pharmacists and others, are educated. The project team stated "Why Avicenna? Avicenna ... was ... noted for his synthesis of knowledge from both east and west. He has had a lasting influence on the development of medicine and health sciences. The use of AvicennaÕs name symbolizes the worldwide partnership that is needed for the promotion of health services of high quality."

Works

Ibn Sina wrote at least one treatise on alchemy, but several others have been falsely attributed to him. His book on animals was translated by Michael Scot. His Logic, Metaphysics, Physics, and De Caelo, are treatises giving a synoptic view of Aristotelian doctrine, though the Metaphysics demonstrates a significant departure from the brand of Neoplatonism known as Aristotelianism in Ibn Sina's world; Arabic philosophers have hinted at the idea that Ibn Sina was attempting to "re-Aristotelianise" Muslim philosophy in its entirety, unlike his predecessors, who accepted the conflation of Platonic, Aristotelian, Neo- and Middle-Platonic works transmitted into the Muslim world.

The Logic and Metaphysics have been extensively reprinted, the latter, e.g., at Venice in 1493, 1495, and 1546. Some of his shorter essays on medicine, logic, etc., take a poetical form (the poem on logic was published by Schmoelders in 1836). Two encyclopedic treatises, dealing with philosophy, are often mentioned. The larger, Al-Shifa' (Sanatio), exists nearly complete in manuscript in the Bodleian Library and elsewhere; part of it on the De Anima appeared at Pavia (1490) as the Liber Sextus Naturalium, and the long account of Ibn Sina's philosophy given by Muhammad al-Shahrastani seems to be mainly an analysis, and in many places a reproduction, of the Al-Shifa'. A shorter form of the work is known as the An-najat (Liberatio). The Latin editions of part of these works have been modified by the corrections which the monastic editors confess that they applied.

Classical and Roman Empire

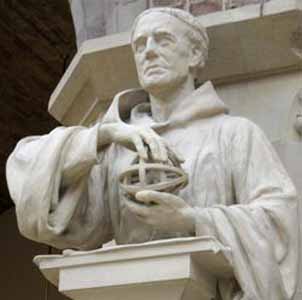

Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus also known as Albert the Great and Albert of Cologne, is a Catholic saint. He was a German Dominican friar and a bishop who achieved fame for his comprehensive knowledge of and advocacy for the peaceful coexistence of science and religion. Those such as James A. Weisheipl and Joachim R. Soder have referred to him as the greatest German philosopher and theologian of the Middle Ages, an opinion supported by contemporaries such as Roger Bacon. The Catholic Church honours him as a Doctor of the Church, one of only 34 persons with that honor.

Albertus was born sometime between 1193 and 1206 to the Count of Bollstadt in Lauingen in Bavaria. Contemporaries such as Roger Bacon applied the term "Magnus" to Albertus during his own lifetime, referring to his immense reputation as a scholar and philosopher.

Albertus was educated principally at Padua, where he received instruction in Aristotle's writings. A late account by Rudolph de Novamagia refers to Albertus' encounter with the Blessed Virgin Mary, who convinced him to enter Holy Orders. In 1223 (or 1221) he became a member of the Dominican Order, against the wishes of his family, and studied theology at Bologna and elsewhere. Selected to fill the position of lecturer at Cologne, Germany, where the Dominicans had a house, he taught for several years there, at Regensburg, Freiburg, Strasbourg and Hildesheim. In 1245 he went to Paris, received his doctorate and taught for some time as a master of theology with great success. During this time Thomas Aquinas began to study under Albertus.

Albertus was the first to comment on virtually all of the writings of Aristotle, thus making them accessible to wider academic debate. The study of Aristotle brought him to study and comment on the teachings of Muslim academics, notably Avicenna and Averroes, and this would bring him in the heart of academic debate. He was ahead of his time in his attitude towards science.

Two aspects of this attitude deserve to be mentioned:

-

1) he did not only study science from books, as other academics did in

his day, but actually observed and experimented with nature (the rumors

starting by those who did not understand this are probably at the source

of Albert's supposed connections with alchemy and witchcraft),

2) he took from Aristotle the view that scientific method had to be

appropriate to the objects of the scientific discipline at hand (in

discussions with Roger Bacon, who, like many 20th century academics,

thought that all science should be based on mathematics).

In 1260 Pope Alexander IV made him Bishop of Regensburg, an office from which he resigned after three years. During the exercise of his duties he enhanced his reputation for humility by refusing to ride a horse - in accord with the dictates of the Dominican order - instead walking back and forth across his huge diocese. This earned him the affectionate sobriquet, "boots the bishop," from his parishioners.

After his stint as bishop, he spent the remainder of his life partly in retirement in the various houses of his order, yet often preaching throughout southern Germany. In 1270 he preached the eighth Crusade in Austria. After this, he was especially known for acting as a mediator between conflicting parties (In Cologne he is not only known for being the founder of Germany's oldest university there, but also for "the big verdict" (der Grose Schied) of 1258, which brought an end to the conflict between the citizens of Cologne and the archbishop. Among the last of his labors was the defense of the orthodoxy of his former pupil, Thomas Aquinas, whose death in 1274 grieved Albertus (the story that he travelled to Paris in person to defend the teachings of Aquinas can not be confirmed).

Roman sarcophagus containing the relics of Albertus Magnus in the crypt of St. Andreas church in Cologne, Germany After suffering a collapse of health in 1278, he died on November 15, 1280, in Cologne, Germany. Since November 15, 1954, his relics are in a Roman sarcophagus in the crypt of the Dominican St. Andreas church in Cologne.

Albertus is frequently mentioned by Dante, who made his doctrine of free will the basis of his ethical system. In his Divine Comedy, Dante places Albertus with his pupil Thomas Aquinas among the great lovers of wisdom (Spiriti Sapienti) in the Heaven of the Sun. Albertus is also mentioned, along with Agrippa and Paracelsus, in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, in which his writings influence a young Victor Frankenstein.

Albertus was beatified in 1622. He was canonized and proclaimed a Doctor of the Church in 1931 by Pope Pius XI and patron saint of the sciences. St Albert's feast day is celebrated on November 15. According to Joan Carroll Cruz, is body is incorrupt.

Albertus' writings collected in 1899 went to thirty-eight volumes. These displayed his prolific habits and literally encyclopedic knowledge of topics such as logic, theology, botany, geography, astronomy, astrology, mineralogy, chemistry, zoology, physiology, phrenology and others; all of which were the result of logic and observation. He was perhaps the most well-read author of his time. He digested, interpreted and systematized the whole of Aristotle's works, gleaned from the Latin translations and notes of the Arabian commentators, in accordance with Church doctrine. Most modern knowledge of Aristotle was preserved and presented by Albertus.

Albertus' activity, however, was more philosophical than theological (see Scholasticism). The philosophical works, occupying the first six and the last of the twenty-one volumes, are generally divided according to the Aristotelian scheme of the sciences, and consist of interpretations and condensations of Aristotle's relative works, with supplementary discussions upon contemporary topics, and occasional divergences from the opinions of the master.

His principal theological works are a commentary in three volumes on the Books of the Sentences of Peter Lombard (Magister Sententiarum), and the Summa Theologiae in two volumes. The latter is in substance a more didactic repetition of the former.

Natural Philosopher

An exception to this general tendency is his Latin treatise "De falconibus" (later inserted in the larger work, De Animalibus, as book 23, chapter 40), in which he displays impressive actual knowledge of a) the differences between the birds of prey and the other kinds of birds; b) the different kinds of falcons; c) the way of preparing them for the hunt; and d) the cures for sick and wounded falcons. His scholarly legacy justifies his contemporaries' bestowing upon him the honourable surname Doctor Universalis.

In the centuries since his death, many stories arose about Albertus as an alchemist and magician. On the subject of alchemy and chemistry, many treatises relating to Alchemy have been attributed to him, though in his authentic writings he had little to say on the subject, and then mostly through commentary on Aristotle. For example, in his commentary, De mineralibus, he refers to the power of stones, but does not elaborate on what these powers might be.

A wide range of Pseudo-Albertine works dealing with alchemy exist, though, showing the belief developed in the generations following Albert's death that he had mastered alchemy, one of the fundamental sciences of the Middle Ages. These include Metals and Materials; the Secrets of Chemistry; the Origin of Metals; the Origins of Compounds, and a Concordance which is a collection of Observations on the philosopher's stone; and other alchemy-chemistry topics, collected under the name of Theatrum Chemicum.

He is credited with the discovery of the element arsenic and experimented with photosensitive chemicals, including silver nitrate.He did believe that stones had occult properties, as he related in his work De mineralibus. However, there is scant evidence that he personally performed alchemical experiments.